LEARNING MODULES

RESOURCES

SLIDE LIBRARY

TEMPLATES

ABOUT US

PARTNERS

VIDEO LIBRARY

LWB INSTITUTE

MICRO MODULES

VxMED

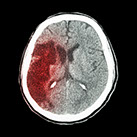

With our local hospital having an upcoming site visit for designation as a Primary Stroke Center, it seemed opportune to introduce the NIH Stroke Scale into the nursing curriculum and to present the Code Stroke Algorithm to students of all the schools. Two scenarios were created with the same learning objectives. In the first scenario, the patient does not have sex-related stroke risk factors when scoring with the CHA2DS2-VASc tool, the risk stratification tool for ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. (5,10) The second case is a patient who falls into a subgroup of patients where the female sex increases stroke risk as described in the 2019 AHA Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke.

In 2014, the American Heart Association published guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women.(1) Since then, research has resulted in the belief that female sex is a risk modifier that varies with age, and at least one author considered the removal of sex as a criterion in the tool.(8) Roy-O’Reilly and McCullough reviewed the effects of the patient’s sex over the lifespan but also discussed experimental evidence showing the differences in ischemic stroke pathophysiology at the level of chromosomal sex. (11) Although determining patient risk for stroke is a moving target, the importance of including sex as a risk factor is important because of the higher incidence and worse outcomes in females. (6)

In order to build scenarios where the presence or absence of sex-related risk factors could provide material for discussion during the debrief, a list of stroke risk factors was created. (See Figure 1 below.) Those factors are included in the CHA2DS2-VASc tool, in bold italics. Some stroke risk factors are now associated with a higher stroke risk in men (3, 9), but none of the CHA2DS2-VASc criteria used to apply the AHA treatment guidelines are related to a higher risk in men. Therefore, it was easier to build a scenario without sex-related risk factors using a male patient.

The case with sex-related risk factors was built around a female patient whose age was in the range where the risk of stroke increased in the female sex. We developed a history that provided indications for anticoagulation therapy and avoided any contraindications to this therapy.

• Figure 1

• Stroke IPE Learning Objectives Description and Worksheet

Included in this section, are two scenarios on the acute care of a stroke patient. In both cases, the students are introduced to the code stroke algorithm, NIH Stroke Scale and TPA administration guidelines. Depending on the curriculum, debriefing could include pathophysiology of stroke, neurological examination, and TPA pharmacology as well as team skills such as mutual support, cross monitoring, and communication.

The scenarios differ in patient characteristics and medical history. Having one patient who is an elderly female with atrial fibrillation and who is on Dabigatran leads to a discussion of the AHA stroke guidelines. The idea of introducing this medication near the end of the scenario history was adapted from a case report where the healthcare team discovered that the patient was on Dabigatran after TPA administration. The timing of the discovery in the scenario allows all students the opportunity to complete their learning objectives.

Many interprofessional scenarios have teamwork skills and a crisis algorithm as the primary learning objectives. The approach taken in this section includes the algorithm but also provides profession-specific learning objectives for each group written by that profession's faculty. In this way, the participants learn about roles and responsibilities of other team members, an important interprofessional competency. This method also allows curriculum goals of the various schools to be met.

For example, in the dress rehearsal video, one can see that while the overarching theme of code stroke algorithm applies to all participants, their individual activities may be concurrent, such as the student nurse starting a second intravenous line on a task trainer while the student doctor elicits a more detailed patient history (task view video of female start at timestamp 10:28). Debriefing can include general themes discussed in the large group and profession-specific topics in break-out groups. Frequently, the curiosity of the participants leads to interchange of information about roles and responsibilities.

As with many institutions, Texas Tech does not train all of the professions represented in these scenarios. In these situations, hospital educators for those professions contribute their perspectives to complete the scenario. For example, Respiratory Therapy is not one of the disciplines of our School of Allied Health, so the learning objectives for that role were obtained from Respiratory Care Educators. The role in the video is played by a facilitator who is both a Respiratory Therapist and a Standardized Patient Educator.

Another time when we turn to hospital educators and healthcare professionals is when our IPE faculty partners are unable to participate due to other commitments or clinical duties. Coordinating schedules is always the most difficult task with IPE projects. When developing the scenarios in this unit, the School of Pharmacy faculty were already committed to other projects, so they referred us to their hospital colleagues.

General learning objectives and scenario flow were established based on the hospital pharmacists' input. For now we will have an actor play the role of the pharmacist in the scenarios until the School of Pharmacy faculty have time to revise the learning objectives and supervise their students' participation. As demonstrated in the video, we have also included a medication room as the pharmacy workspace in preparation for the participation of pharmacy students.

Male Scenario

• Stroke IPE Learning Objectives Description and Worksheet

• Family Member Role Male Scenario

• Faculty Overview Male Scenario

Female Scenario:

• Stroke IPE Learning Objectives Description and Worksheet

• Medication List for Female Scenario

• Faculty Overview Female Scenario

Supporting Material:

Disclaimer: The AHA recommends that all organizations develop local algorithms, order sets, etc, The ones below are only examples. For other examples please see the AHA Clinical Tools library reference #.

• NIHSS Scale (See reference # for NIH Stroke Scale Information)

• Rapid Response Team Standing Delegation Order

• TPA Consent (See reference # for student script in obtaining consent)

References:

• 2019 Atrial Fibrillation Update to AHS/ACC/HRS Guidelines

• 2019 Update to 2018 Acute Ischemic Stroke Guidelines

• AHA Stroke Clinical Tools Library

• Refining Clinical Risk Stratification for Predicting Stroke

The run through of a scenario prior to using it with students is always important but never more so than with interprofessional groups. Differences in perspectives exist not only in regard to patient care, but also to the simulation processes. In these scenarios, we are introducing new information to the students, so much guidance was provided by the facilitators.

Note the quantity of patient equipment and the added task trainers used in a small room, with up to 4 providers present simultaneously. Various items had to be relocated to accommodate work flow and camera angles.

*Due to the nature of recording these demonstrations with cameras installed in the ceiling of the Simulation Center rooms, there are multiple camera views to be viewed for the male and female demonstration.

*The video clips below are labeled to correspond to the specific learning objective that is accomplished during the clip.

*We highly recommend that you used high speed Internet when viewing the following videos.

#1 follows code stroke algorithm

#2 assess eligibility for TPA

#3 obtains consent for TPA

#1 recognizes FAST symptoms

#2 use code binder and follow algorithm

#3 documents code stroke

#1 applies mask

#1 Tanner's educational plan w daughter

#2 discovery of medication list, coumadin is not universally recommended for a. fib

#3 woman's behavior

SOM

SON

RT

DEBRIEF

Below is a list of references used for this case development.

1. Bushnell C, et al. On behalf of the American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke in Women: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. Published online February 6, 2014. http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/early/2014/02/06/01.str.0000442009.06663.48.

2. Chen LY, et al. CHA2DS2-VASc Score and Stroke Prediction in Atrial Fibrillation in White’s, Blacks, and Hispanics. Stroke. 2019;50:28-33. DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021453.

3. Gall, et al. Focused Update of Sex Differences in Patient Reported Outcome Measures After. Stroke. 2018;49:531-535. DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018417.

4. Get With The Guidelines® - Stroke Clinical Tools. (2018, May 29). Retrieved March 11, 2020, from https://www.heart.org/en/professional/quality-improvement/get-with-the- guidelines/get-with-the-guidelines-stroke/get-with-the-guidelines-stroke-clinical- tools#.Vu8hHeIrI-U.

5. January CT, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2019;140:e125-e151. DOI: 10.1161/CIR0000000000000665.

6. Lane DA, et al. Use of the CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED Scores to Aid Decision Making for Thromboprophylaxis in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation. 2012;126:860- 865.

7. Lip G, et al. Refining Clinical Risk Stratification for Predicting Stroke and Thromboembolism in Atrial Fibrillation Using a Novel Risk Factor-Based Approach. Chest. 2010;137:263-272.

8. Madsen TE, et al. Impact of Conventional Stroke Risk Factors on Stroke in Women: An Update. Stroke. 2018;49:536-542.DOI: 10.1161/STOKEAHA.117.018418.

9. McDermott LM. Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: Key Points. American College of Cardiology. Nov 6, 2019. acc.org

10. Nielsen PB, et al. Female Sex Is a Risk Modifier Rather Than a Risk Factor for Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation: Should We Use a CHA2DS2-VA Score Rather Than CHA2DS2-VASc? Circulation. 2018; 137:832-840. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029081.

11. NIH Stroke Scale/Score (NIHSS). (n.d.). Retrieved March 11, 2020, from https://www.mdcalc.com/nih-stroke-scale-score-nihss

12. Pfeilschifter W, et al. Thrombolysis in a Stroke Patient on Dabigatran Anticoagulation: Case Report and Synopsis of Published Cases. Case Reports in Neurology. 2013;5:56-61. DOI:10.1159/000350570.

13. Poorthuis MHF, et al. Female- and Male-Specific Risk Factors for Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2017:74(1):75-81. DOI:10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3482.

14. Powers WJ, et al. on behalf of the American Heart Association Stroke Council. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50:e344-e418. DOI: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000211.

15. Roy-O’Reilly M, McCullough LD. Age and Sex are Critical Factors in Ischemic Stroke Pathology. Endocrinology. 2018,159(8):3120-3131. DOI. 10.1210/en.2018-00465.

16. Thomas L, et al. Variability in the Perception of Informed Consent for IV-tPA during Telestroke Consultation. Frontiers in Neurology. 2012;3(28):1-6. DOI:10.3389/fneur.2012.00128.

Introduction

Overview

Videos

Resources

All original content © 2014 TTUHSC LWBIWH,

All rights reserved.